Interview:

A Conversation with Amiri Baraka

The New Puritan ReView

Minneapolis, MN

February 1992

Exploring the creative process that connects performing artists with writers and readers alike.

The New Puritan ReView

Minneapolis, MN

February 1992

Exploring the creative process that connects performing artists with writers and readers alike.

The syntax of this piece is admittedly a bit odd; chalk it up to another layout that was damaged or lost over the years. Then again, it was blind luck – or providence, depending on what you believe in – that I was able to document this brief conversation with the person who single-handedly inspired me to start writing in the first place. When I heard Amiri Baraka was going to speak at the Weyerhauser Chapel on St. Paul’s Macalester campus, I made sure I had the day off from my day job. I brought my semi-trusty recording Walkman, in the hopes that I would be able to record his talk, and possibly even get a few minutes of his time, to conduct an interview of sorts – even if it might have been only an excuse to talk with the man again.

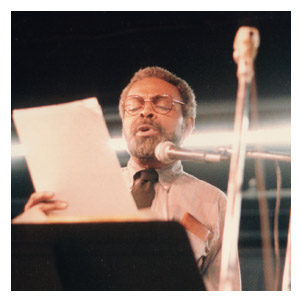

We had, in fact, met a couple of times previously – once at a reading he delivered at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1983; and again in NYC in 1985, on his 50th birthday, when he performed with his jazz outfit Blue Ark (which is also where the photos on this page are from). It was in NYC, as I had brought along a few more of his books for him to autograph, he joked that once he signed them, I could sell them for a lot of money some day. Hmmm… if I had been motivated by profit, I definitely should have picked up the “It’s Nation Time” LP he had with him that day – what was I thinking? At any rate, I suggested that if his signature was worth money, that would mean he was doing well, but I was also quick to assure him that I would never get rid of them in my lifetime. When I told him he had inspired me to write as early as the 4th grade, he laughed, almost embarrassedly, and exclaimed, “Oh man, you make me feel ancient!”

I meant it when I said I wouldn’t get rid of those books. Truth be told, I think I need to read them a few more times. Especially now, considering that while I was encoding this interview for the internet, I learned he had taken leave of the planet only a few hours earlier.

Damn.

I mean, first of all, now I can’t share this with him – this digitized version, that is. A selfish regret, perhaps, but I also think he might have dug seeing it in this form. I gave him a few physical copies of the ‘zine back in the day, but I don’t even have one of those anymore, so I hope that what remains here might at least play a bit part in helping share some of his life story. Considering that he was gracious enough to grant me a private interview after a full day of public activity, I really hope I didn’t waste his time, considering I had no prepared interview questions, and was just going off what I knew about him through accounts in the press over the past 25 years. And of course, his books.

Every time we had met in the past, I felt there was a zen quality about him that transcended whatever else was going on at the moment – that he was giving you all of his time, and all of his attention. Following his talk at Macalester, he met with a handful of college press people, various student body groups, and I just kind of tagged along, trying to meld into the crowd each time, until finally, it was just the two of us, and he invited me up to the guest room where he was staying, for his last interview of the day. I was the only person who had no appointment scheduled with him. That didn’t seem to get in the way of him giving even more of his time, albeit to a scruffy white kid who peddled a self-published, self-opinionated xerox magazine about alternative music. I like to think that says something about the kind of man I perceived him to be – personable, kind, gracious, and unapologetic.

I’m pretty certain that I only transcribed the parts of our conversation that seemed pertinent to social issues, and left out personal conversation. For example, I recall that his curiosity was piqued when I informed him that this interview would appear in an issue which would also feature an interview with Nation Of Ulysses. “Are they Muslim?”, he inquired, He seemed slightly baffled, and possibly amused by my description of the group and their faux-propagandizing manifestos on the current state of music.

On a related note, I remember that we discussed how Malcolm X had reassessed his own relationship with young white college students back in the day, and I wondered if we weren’t seeing a resurgence of that kind of socio-political alliance within the current generation. Perhaps that would have been interesting in this transcript, but it wasn’t recorded, as our conversation was much longer than what is presented here. This is all that remains from that day, with only this preface to put it in any context. In the end, I hoped that what was printed might be inspirational to young artists and anarchists alike. As Jenny Holzer once stated, “If you aren’t political your personal life should be exemplary”. In my mind, Amiri Baraka succeeded on both levels. Sadly, in the present day, I can’t think of anyone who might be capable of carrying the torch forward, and continuing the cultural social work to which Amiri Baraka dedicated his entire life.

On a final personal note, it bugs me that I won’t get to see him again. As it turns out, the last chance I had for that would have been in 2011, when he gave a talk at the University Of Oregon – only I didn’t know about it at the time. I won’t be able to ask him to sign any more books, either. But the ones I have aren’t going anywhere, count on that.

Rest In Peace; 9 January 2014

![Amiri Baraka backstage in NYC 1985 [photo 2]](https://sonicarchives.com/wp-content/uploads/baraka3.jpg)

[This is pretty much just the pre-edited, raw interview / conversation; most of which ended up in the published article, as it appears here.]

Q Do you find it difficult to live under government surveillance?

A You don’t really have a choice. I mean, you do have a choice, but it’s not a choice you’d make. It’s a question of if you know – given the history of the situation – that if you do certain things, there’s going to be certain responses from the powers that be. I think that you have to weigh that when you’re doing it. If you don’t weigh it, then you’re being irresponsible.

Q When did you first become aware that you were being watched?

A The Freedom of Information Act papers confirmed what was happening, in the sixties and the seventies. For me it goes back to being in the Air Force. That’s when all of my Freedom Of Information Act stuff begins, when I was an Airman Second Class Stationed in Puerto Rico. The first mention in there when they charged me with being a Communist, of some anonymous form as I always think – I don’t remember being a Communist. I was given an undesirable discharge from the Air Force – it begins there. Then, various kinds of things you’re involved with – you see that they have listings; that they’ve taken note of this, and taken note of that through the years, and although they claim they don’t do it anymore, obviously they still do.

Q Had you already begun writing at that time?

A I began writing in high school actually, in terms of a little bit of scribbling. I wrote a little bit in college, but it was in the service that I actually began to write and began to really educate myself, in great leaps and bounds. The two years that I spent in the Air Force was – I think – the most intensive period of self-education for me.

Q At that time, would you say your work had begun to take on a political nature, or was it more of an artistic ambition?

A I’ve never had anything but the artistic question of feeling, the question of wanting to express myself, but then that gets to be more and more specific.

Q So you wanted to be a writer, but not necessarily any kind of spokesperson?

A Oh yeah. It was about expression, really – the point that I have things that I want to say, I have feelings that I want to express. I didn’t try to define what kind of category those things would come under, that was what it was.

Q By the time you had changed your name from Leroi Jones to Amiri Baraka, what aspects of your previous lifestyle did you have to leave behind?

A By that time, it was sort of after the fact. I had gotten away from the whole circumstances that I had considered anti-political – namely the whole Village / Lower East Side thing – and had got a divorce, moved to Harlem, and involved myself even more intensely in that struggle. So, by the time the name change came I had been involved in I guess a more intense level of involvement in the Liberation Movement. So, the name change – the name was given to me by the man who buried Malcolm X – came as a kind of confirmation of that activity, not an initiation of it. That’s all it was. I could accept the idea of being closer to Africa – even though the name first given to me was Amear Baraka, which was Arabic, but I Swahili-ized it, banto-ized it and it became Amiri Baraka. Then I was given the name Immamu – which was a title – which I dropped. People still call me that – certainly in Newark. That was just a confirmation of the particular stance that I was taking.

Q Do you find that people generally tend to misconstrue what you’re trying to say?

A I think in political ideas, they do that all the time to make you seem like you’re half-brained, or you’ve got some kind of oppressive ideology. They do it usually just to narrow the range that your philosophies can actually reach, to limit you. Sometimes they take your ideas and use ’em and then attribute backward versions of those ideas to you. The whole intensity of class struggle in the arts, comes from critical writing; see, that’s where the class struggle is. Various critics represent this side or that side, they represent the forces of good, the forces of evil, and you always see them working out in public.

Q Have certain ideas of yours been more greatly distorted than others?

A I think that people tend to cover and then to distort. For instance, now these people come out with the idea of “performance poetry”, and it was just like, a fake idea. When we started reading poetry the way that we thought it should be – according to living rhythms: that the poetry was song actually, that it was an emotional kind of confrontation, not just an intellectual one, or one about alienation or extraction. Then people start saying, Wow, if they’re reading poetry like this then they must be performing – then they create a category called “performance poetry” of which these few people are the leaders. At the same time what they’re trying to do is actually distort what you’re doing – as if performing the poetry was an act that was not endemic to poetry itself, but that it was some kind of thing you were adding on to it; rather than seeing poetry essentially as a score. Written poetry is something like a score of written music. It has to be actually played, by the person, by the instrument.

Q Wouldn’t you agree that there is a paradox involving the emphasis on education, whereas the public school system is fundamentally trying to condition people?

A Well, see that’s the point – you emphasize education, you emphasize the fact that people have to take the task of changing these schools as a revolutionary item. It’s not that you just say that education is no good because it’s created by the bourgeoisie. Bourgeois education is no good – although god knows that you have to have it to make it in this kind of bourgeois world. What we’re saying is that you have to forcefully turn the focus of education so that it begins to create self-consciousness, so that it begins to uncover, not cover. That’s why we want the youth to go into these schools, go into the public schools, grammar schools, high schools, colleges – to go in these schools and grapple with these curriculums; to struggle with these fascist forces within the schools and to turn ’em around, so that it’s a question of fighting for some new directions in the schools, not just going there accepting the status quo.

Q There seems to be some difficulty in accepting that the purpose of public education is to simply train people to fit into the existing class and economic structures.

A That’s what they are for, you have to impose another kind of focus on it. That’s why we talk about cultural revolution – we have to actually try to make cultural revolution in these schools, in these institutions, otherwise they would do what they do normally – turn out Americans of the most backward ideological development.

Q The obvious answer to that would be to enter these institutions and be able to exploit the resources for information they contain.

A Yeah, again, to the extent that school is a combination of resources. They have to be utilized, they can be accessed, but you have to make certain that you are not being trained by those institutions, because that’s the point – to train you. You have to make sure that you can use them as a point of demarcation for your education. What they say, what they want, as opposed to what I’m finding out, and what I’m doing. Use it as a point of departure for real development.

Q Do you agree that the nature of our society prohibits many – if not most – working class citizens from being able to continue their education beyond high school?

A On one hand you have what are called advanced workers – people who might never go to college but who say study, study, study, study, and might turn themselves into advanced revolutionaries, advanced social political thinkers. Then there’s people who go to college, and all that college does is to provide them with a method of being co-opted into the system. Most people will never go to college, therefore you have to emphasize the importance of the advanced workers, the people who are not in college, but who are still endeavoring to educate themselves. At the same time, you cannot dismiss formal education. You have to look at it dialectic-ally and suggest how it can be improved and what must be done to change its class base, to change its class focus – what it wants, what side it’s on; because the schools now generally are on the side of the rulers.

Q Again, we’re simply talking about a fair exchange between what one puts into the system, and what one expect to get back.

A Yeah, but you have to assault it – the educational system has to be confronted and challenged and changed and you getting what you want out of it is part of that. I don’t think that you can get what you want out of it unless you see that the main focus of the current education system is negative. I mean, they’ve turned most of these schools into…almost vocational schools – it’s like the school is like the unemployment pages or something. You get out and you’ve got a job, and that’s the whole function of it. But the function of college is supposed to be to teach you how to think, and that’s a wholly different priority.

Q So no matter how you look at it, would you say that this people’s revolution is imminent?

A I think that it depends on the degree of unity and the organization of the people. The question of people’s democracy in America – public control of the corporations, banks, utility companies, can that be brought on peacefully, or is that gonna take war? Some of it will come non-violently, the rest of it’s gonna have to come with the assault of the people, which is going to be bloody. They’re not asking for anything else, because they’re not going to do anything else, but exacerbate it until it does come. Some of them actually believe that they’ve got the tanks and guns to kill people – they welcome it.

© J.Free / The New Puritan ReView; February 1992; 2025

All photos © J.Free; 1985:

Amiri Baraka • Jazz Coalition Center, NYC 1985

Blue Ark • performing at Amiri Baraka’s 50th birthday celebration • Jazz Coalition Center, NYC 1985

L to R: Amiri Baraka (voice); Rahman Herbie Morgan (tenor saxophone); Grachan Moncour III (trombone); Rudy Walker (drums)

Amiri Baraka • backstage Jazz Coalition Center, NYC 1985

American Music Club Daniel Ash Babes In Toyland Amiri Baraka The Beta Band Bikini Kill Frank Black Concrete Blonde Cordelia’s Dad Mike Doughty Edison Shine Fugazi God Bullies Guided By Voices Hole Home Hüsker Dü The Jesus Lizard Jonestown Killdozer King Missile Mecca Normal Bob Mould The Nation Of Ulysses Nice Strong Arm Pegboy Pseudonymphs Sci-Fi Western Sebadoh Skinny Puppy Skinny’s 21 Technique Niquée The Wedding Present Zuzu’s Petals